Designing Sentry's cross-region replication

When we started designing multi-region Sentry, we didn’t plan on having replication between regions. However, as we got farther in the design process it became clear that because of where our silo boundaries would be, we would need data replicated between regions to facilitate looking up in which region an organization was in, or validating API tokens. While these operations could be completed with Remote Procedure Calls (RPC). The latency, atomicity and resiliency impacts of these high-volume RPC operations wouldn’t be acceptable, and we needed a solution that would be more efficient and more correct.

As the scenarios where we would use cross-region replication became more clear we collected the following requirements:

- We needed resiliency to network failures. Replication would be disrupted by networking issues so we needed the system to work off of last-known information. During a disruption replicated data could become stale, but wouldn’t expire.

- We wanted to be able to backlog changes without risk of an in-memory system overflowing and failing.

- We wanted a solution that could reliably replicate changes eventually. Data loss should be rare, and we shouldn’t need to manually intervene to correct divergent state caused by networking or unavailability in other parts of the system.

- We wanted a solution that we could gradually integrate into the application and validate replication both in CI, and in production before relying on it for customer traffic.

- We didn’t want workloads from one customer to impact replication of another customer’s data.

Our requirements led us to looking at solutions that would provide an eventually consistent model that leveraged durable data stores.

Scenarios where we use cross-region replication

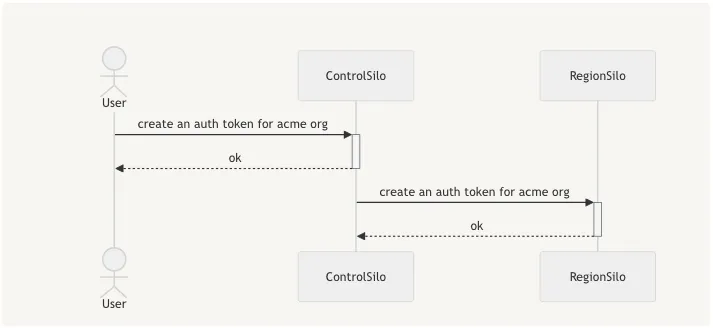

We use cross-region replication between our region silos, and control silo. Replication is performed in both directions but for different operations.

For example, when an organization creates a new API token, that token needs to be present in both the control silo, and in the region where the organization is located.

Authentication tokens are centralized in Control Silo, so that we can locate the organization tokens, work against control silo resources, and so ensure that all tokens are unique with database constraints. We need to replicate the organization’s token to region silo so that it can be used to authenticate requests made there. Later, when the token is deleted, the user will remove it from Control Silo, and replication should update the relevant region.

We also use cross-region replication to push organization membership from the regions into Control Silo. That allows us to apply membership role permissions to organization resources in Control Silo (like Authentication tokens and Integrations).

Evaluating existing solutions

With a better understanding of our requirements, and workflows, we began evaluating existing solutions for how much complexity and infrastructure they would require in addition to meeting our functional requirements.

Postgres Replication

Postgres comes with built-in capabilities to stream data from one database server into a replica that supports read operations. Postgres replication would have met our consistency requirements and would have required the smallest number of application changes. Postgres replication was not selected for a few reasons:

- Postgres can only replicate at the table level. This would result in data being ‘over-replicated’ to regions. If a US organization creates an Authentication Token, there is no reason for that token to be replicated to other regions.

- Postgres replication could not be used for the Region → Control path as a replica cannot have multiple primaries/leaders, and with each region replicating data back to control, we would have that scenario.

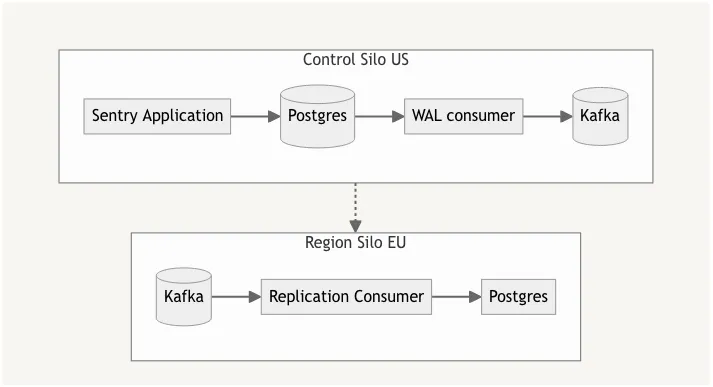

Change Data Capture (CDC) and Kafka

Because naive Postgres replication would have resulted in over-replication, we could build an application that consumed Postgres’ streaming replication data, and converted changes into Kafka messages. A Postgres replication consumer would allow us to selectively replicate changes to only the regions that were relevant, and transform queries into relevant domain actions when creating Kafka messages.

CDC would provide atomic operations and we could easily backlog operations in Kafka for as long as required. Regions would use mirror maker to replicate topics, or use a multi-region Kafka

We decided against this approach because of the complexity. We would need to operate additional Kafka clusters, maintain and operate a WAL consumer, Kafka producers, consumers, and translation code from WAL operations into replication changes.

Outboxes

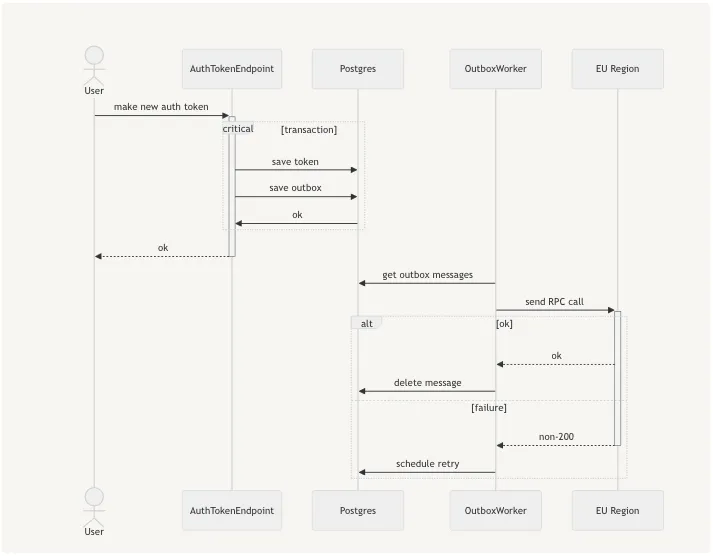

Transactional Outboxes are a distributed systems pattern that fit our use case perfectly. As the application makes changes that need to be replicated, it can save an ‘outbox’ in the same postgres transaction as the change - providing the atomicity we wanted. In the background, a worker pulls tasks from the outbox table and runs handlers to apply the necessary replication action via RPC. With this design we would be able to provide eventual consistency with at-least-once delivery semantics.

When delivering an outbox message our implementation assumes that any failures will raise errors, and that if an outbox handler completes successfully, that the replication operation is complete.

Outbox Storage

In order to reach our customer isolation requirements, we tailored our outbox storage around the ideas of shards and categories. Within the outbox storage we divide messages into multiple shards based on the scope of a message. Message scopes are generally bound to the Organization or User. Messages also have a category and object_identifier which defines the type of operation being performed, and the record the operation is for.

With these attributes we’re able to process messages for each ‘shard’ in parallel independently from other shards. Furthermore, because messages are delivered idempotently, we coalesce messages with the same category and object_identifier. Coalescing messages allows us to short cut replication by not transferring all of the intermediary stages.

Unfortunately because of how our Postgres databases are partitioned, we’ve needed to create several outbox tables in order to preserve transactional semantics.

Delivering outbox messages

When outbox messages are delivered, the outbox delivery system will call all registered handlers for the outbox category. The handler for organization authentication tokens looks like:

def handle_async_replication(self, region_name: str, shard_identifier: int) -> None:

from sentry.services.hybrid_cloud.orgauthtoken.serial import serialize_org_auth_token

from sentry.services.hybrid_cloud.replica import region_replica_service

region_replica_service.upsert_replicated_org_auth_token(

token=serialize_org_auth_token(self),

region_name=region_name,

)Because all of our outbox handlers use RPC for replication we had to invest the time to make our RPC operations idempotent. A simple way to make operations idempotent is to transfer a snapshot of the current state instead of the changes to a object. By sending the entire object we ensure that state will converge and become consistent.

Ensuring consistency

Because our consistency relies on outbox messages being created at the same time as record changes, we could easily get into scenarios where application developers forget to create an outbox record when they persist a change to the source record. To prevent this scenario from occurring we did two things.

The first is to update our ORM models so that .save() and .update() apply both the transaction and outbox message generation. This covers scenarios where we modify records and then persist them but still leaves us vulnerable to missing outboxes created by bulk queries.

For example, the following operation would break cross-region consistency

from sentry.models import OrganizationMember

OrganizationMember.objects.filter(id=member_id).update(user_id=None)To handle this scenario, we elected to build tooling that audits the SQL emitted by the application during tests and use a set of heuristics to find queries that could cause consistency issues. The above query would be detected by our test suite tooling and emit the following error:

_______________________________________ ERROR at teardown of OrganizationMemberTest.test_consistency ________________________________________

tests/conftest.py:104: in audit_hybrid_cloud_writes_and_deletes

validate_protected_queries(conn.queries)

src/sentry/testutils/silo.py:520: in validate_protected_queries

raise AssertionError("\n".join(msg))

E AssertionError: Found protected operation without explicit outbox escape!

E

E UPDATE "sentry_organizationmember" SET "user_id" = NULL WHERE "sentry_organizationmember"."id" = 7

E

E Was not surrounded by role elevation queries, and could corrupt data if outboxes are not generated.

E If you are confident that outboxes are being generated, wrap the operation that generates this query with the `unguarded_write()`

E context manager to resolve this failure. For example:

E

E with unguarded_write(using=router.db_for_write(OrganizationMembership):

E member.delete()

E

E Query logs:

E

E SELECT 'start_role_override_30'

E UPDATE "sentry_organizationmember" SET "user_is_active" = true, "user_email" = 'd1006c8c057a462ba94133e7ac40f488@example.com' WHERE "sentry_organizationmember"."user_id" = 6

E SELECT 'end_role_override_30'

E SELECT "sentry_regionoutbox"."id" FROM "sentry_regionoutbox" WHERE ("sentry_regionoutbox"."category" = 3 AND "sentry_regionoutbox"."object_identifier" = 7 AND "sentry_regionoutbox"."shard_identifier" = 4554241598816256 AND "sentry_regionoutbox"."shard_scope" = 0) LIMIT 100

E DELETE FROM "sentry_regionoutbox" WHERE "sentry_regionoutbox"."id" IN (15)

E RELEASE SAVEPOINT "s8377039552_x80"

E SAVEPOINT "s8377039552_x85"

E SELECT "sentry_regionoutbox"."id", "sentry_regionoutbox"."shard_scope", "sentry_regionoutbox"."shard_identifier", "sentry_regionoutbox"."category", "sentry_regionoutbox"."object_identifier", "sentry_regionoutbox"."payload", "sentry_regionoutbox"."scheduled_from", "sentry_regionoutbox"."scheduled_for", "sentry_regionoutbox"."date_added" FROM "sentry_regionoutbox" WHERE ("sentry_regionoutbox"."id" <= 15 AND "sentry_regionoutbox"."shard_identifier" = 4554241598816256 AND "sentry_regionoutbox"."shard_scope" = 0) ORDER BY "sentry_regionoutbox"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 FOR UPDATE

E RELEASE SAVEPOINT "s8377039552_x85"

E SELECT 'end_role_override_28'

E UPDATE "sentry_organizationmember" SET "user_id" = NULL WHERE "sentry_organizationmember"."id" = 7

E ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^Because we’re auditing SQL logs we can’t easily point to the specific line of code, but we can provide the query logs and where the problem query is.

Rollout

Once we were confident that outboxes were being created correctly and state between the replica and source tables would reach consistency, we incrementally enabled outbox message creation and processing in production well before we began the process of splitting the database or application up. This allowed us to have confidence that the outbox system was behaving correctly, and establish baselines for performance, and message delivery.

During the rollout period we were also able to gain experience adding and removing message types as our design and implementation became more self-evident.

Problems along the way

With almost 1 billion outbox messages delivered, the system has been performing well, but hasn’t been without a few problems along the way.

Initially we were using outboxes for delivering webhooks that are received from third-party integrations like GitHub. Delivering these webhooks to the relevant regions can incur a few seconds of latency. When we process an outbox message, we lock the row within a database transaction to prevent concurrent access. However, the delivery time on many webhooks exceeds our transaction timeout, resulting in slow and uneven message delivery. Instead of relaxing our transaction timeouts we chose to rebuild webhook delivery with different storage that didn’t require row locks.

One challenge we haven’t solved yet is being able to detect and prevent outbox loops. It is entirely possible for the handler of an outbox message in a region to perform an action that creates outboxes in control silo that are then delivered to the region potentially creating an infinite loop. We had one such loop form during an incident. While we’re able to detect these loops and resolve them after they happen it would be better to know that such events are impossible.

Outside of those problems, transactional outboxes has proven to be a resilient and scalable design that we’re hoping to leverage more in the future.